We Can Do More: Challenges of Iranian Students Wishing to Study in America

Please read the new and updated version of this report, published in February 2014 with the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

I remember when I wanted to start the application process, my friend who was in USA at the time told me that you have to get shoes and nerve made of iron to start this process. Once I started the process I realized what he meant!

— An Iranian PhD student in America, specializing in materials science and engineering

Over 250,000 — a quarter million — American college students study abroad each year.[1] They apply for passports, and receive student visas. Parents transfer money to bank accounts for food and rent. Transcripts are sent, and new international phone plans are purchased. For students who have studied in foreign countries, these familiar activities are often tinged with excitement — mere formalities that exist between them, and a safe, fun-filled semester or year of living and learning thousands of miles away from home.

However, consider another scenario. What if significant impediments existed that hindered the ability of students to travel and study with ease, and in safety? What if they were unable to:

- Obtain a visa — unless they travelled to an embassy in a foreign country, and spent several months of income for flights, lodging, and processing fees?

- Submit applications, test scores, and transcripts to a foreign university — without illegally purchasing a debit card on the black market, and at exorbitant prices?

- Depart for their study destination — except by paying over a year’s worth of household income to the government, or even turning over the deed to their car or house, as a “guarantee” to ensure they return?

- Easily receive money from their parents in emergencies, or for living expenses and tuition?

- Travel home for holidays, or the death of a loved one, because this tedious process would have to be repeated again, and with significant delays?

And finally, what if these students had to experience all this (and more), but were desperately seeking to study abroad — education being the sole means to not only leave their country and experience the broader world, but also escape political and social oppression?

The above scenarios are not fictional — rather, they have been faced by the nearly 7,000 students from Iran who currently study at American universities. While Iranians once constituted the largest group of foreign students in the United States (Iran held the #1 spot from 1975-1983, peaking at 51,000 students in 1980),[2] the severing of diplomatic ties after the 1979 Islamic Revolution, and more recent economic sanctions, have provided Iranian students with unprecedented challenges on the road to American education. Nonetheless, their determination has prevailed: Enrollment at American universities has doubled since 2009, and in 2011-2012, there was a 24% increase in students over the previous academic year.[3]

The challenges of Iranian students have not been ignored, and are not unknown. Multiple entities — both within the United States government, and lobbying and student groups — have sought to ease them. In May 2011, in response to feedback from student and university organizations, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton addressed Iranian students directly, announcing that they would be eligible for multiple-entry visas — allowing easy departure from and return to the US for holidays, family emergencies, and academic conferences. Because, she said:

I want you to know that we are listening to your concerns…As long as the Iranian government continues to stifle your potential, we will stand with you. We will support your aspirations, and your rights. And we will continue to look for new ways to fuel more opportunities for real change in Iran.

— “Changes to Iranian Student Visa Validity.” U.S. Department of State. May 20, 2011[4]

Despite their small numbers (China, by comparison, has 200,000 students in the US), Iranian students bring a lot to the table, and hold several distinctions among the US foreign student population:

- According to the Institute of International Education (IIE) — over 80% of Iranian students in the United States study at the graduate level — the highest percentage of any country.[5]

- Similarly, over 75% (every 3 out of 4 Iranian students) are enrolled in the critical STEM fields (engineering, math and computer science, and physical and life sciences). Again, the highest percentage among the top 20 countries that send students to America.[6]

- Astoundingly, in a survey of nearly 1,000 Iranian PhD graduates in the STEM subjects and social sciences — conducted by the government-run National Science Foundation (NSF) — 89% indicated that they “intended to stay” in the United States (employment permitting). Known as the “stay rate,” this number is also higher than any other country.[7]

The implications of these statistics will be explored later — however, they demonstrate that Iranian students are highly motivated, study in critical fields, and wish to contribute to America. Despite this — a full accounting of the problems they face has never been given — limiting the ability of policy makers and university administrators to fully grasp the breadth of their challenges, provide understanding and help, and craft meaningful solutions. Moreover, although significant overtures have been made to ease their mobility experiences — like with multiple-entry visas — surveys of Iranian students indicate that this new directive is unevenly applied, and subject to broad inconsistencies.[8]

In short, We Can Do More: To engage these students; to provide them with the concern, care, and opportunities we would want for ourselves, our friends and classmates, and our family members; and to advance the human right of global mobility — in this age of technology and human interconnection — for students to travel and study with ease and peace of mind, wherever their educational aspirations take them.

To this end, this paper — based on extensive research of open source and historical material, personal interviews, and surveys — will present the challenges of Iranian students, along with positive avenues for reform. While not all of their challenges can be solved, it is hoped that a full accounting of them can prompt action on some level, and ease the mobility experiences of Iranian students wishing to study in America. In the end, this paper is not about Iran, or any country — but simply, it stems from a desire to ease global student mobility for all humans, and provide a voice, contribute knowledge, and help in an area where it has not been fully done.

Overview and Recommendations

In short, what are some concrete steps that can be taken to remedy the problems Iranian students face? In reference to the opening quotation by the PhD student — how can we soften the “nerves of iron” Iranian students are forced to forge as they attempt to study in America?

Although the totality of their problems cannot be solved, there are several, minimally invasive steps that American stakeholders can take, which would not only significantly help Iranian students and ease their experiences, but also contribute to positive change within Iran. These recommendations focus on four areas: University application fees and admissions, standardized testing, visa appointments and irregularities, and women.

By analyzing these four issues, we can understand not only the breadth and specifics of challenges Iranian students face, but also viable paths for reform. Although each section contains unique aspects of the Iranian student experience, they are structured independently and can be read individually. This will be followed by two further sections: A history of US-Iranian educational engagement — including current student trends, policies, and stakeholders — and a selection of student stories and quotations related to the issues above. And, a conclusion.

1. University Application Fees and Admissions

The National Association for College Admission Counseling (NACAC) — the largest organization of admissions professionals, with a membership of more than 1,500 colleges and universities — can take concrete steps to implement an “admission application fee waiver,” not just for Iranian students, but all international students. This would be in addition to the waiver, created by the NACAC, that is already in place for disadvantaged American students.[9]

While application fees distinguish serious applicants, and serve as a source of revenue — due to economic sanctions against Iran’s banking sector, Iranian citizens cannot conduct online transactions, facilitated by Western banks. However, because application fees must be paid on university websites, Iranian students are forced to illegally purchase foreign, pre-paid debit cards, at marked-up prices, resulting in significant logistical and financial hardship.

One student, in response to a self-administered survey, conveyed his experiences:

I had two issues with application fees. First, I was not able to pay on my own since I did not have credit card in Iran and it was really hard to pay by credit card from Iran…Second issue is that the application fee is high for students which limits the number of universities that they can apply. At least this is what happened to myself.

— An Iranian PhD student in America, specializing in engineering

To demonstrate this reality — pictured below is a popular website Iranian students use to obtain debit cards. Purchased in neighboring countries, and smuggled into Iran, they are openly sold on the Internet at 20-30% premiums. Meaning, if an Iranian student purchases a $1000 pre-paid card, it is often sold for $1300. Other challenges exist: Although pre-paid, these cards must be obtained through banks, and registered with valid names and addresses. When used outside the country of origin (like by a student in Iran), they can be blocked by the issuing banks, necessitating the use of privacy software to mask computer location. Some students are unaware of this, and can incur significant financial loss. Simply, from the very start of their educational journey to America, Iranian students are forced to engage in broad illegality, and experience significant financial hardship.

Notice “TOEFL” and “GRE” listed as reasons to purchase a card. The reality is that such cards are necessary to pay for educational services, including application fees.

To add to this fact, due to deteriorating exchange rates between the Iranian rial and US dollar, the purchasing power of local currency has fallen — which has made Western goods and services three to four times more expensive than in recent years.[10] Simply, paying in dollars — which is necessary for application fees, standardized tests and score reports, and international travel — has become a very expensive process. As one student said:

We are not able to have international credit cards. We have to pay extra amount of money to people having credit card. Dollar is going up rapidly. For example: Two years ago one $ was about 1000 tomans, but now one $ is about 3500 tomans. Really, application fees take up a large percentage of our budget.

— An Iranian, engineering master’s student in America

Personal initiative to help Iranian students pay application fees is not a viable option either: According to Article 560.206 of the Iranian Transactions and Sanctions Regulations (ITSR) — developed by the U.S. Department of the Treasury to regulate sanctions laws — the export of “goods, technology, or services” to Iran, from American individuals or entities, is subject to strict controls and licensure.[11] Charitable donations are similarly regulated. This broad article of the ITSR — originally promulgated into law in 1995, through Executive Order 12959 — also served as the impetus for Western banks to cease payment processing from Iran.[12] One student summed up the situation:

Because of the sanctions, Iranian students inside Iran cannot have and use international credit cards (such as Visa/Mastercard) for their payments, involving the application fees. They have a hard time doing this through some intermediate companies that provide them with virtual credit cards, with a very high price. By price, I mean the relative value of US Dollar with respect to Iranian Rials, which is getting worse and worse these days under the intense sanctions.

— An Iranian PhD student in America

Given their overwhelming desire to leave the country, however, Iranian students routinely apply to eight or even ten universities, with 15-20 not unknown. Coupled with the debit card and exchange rate issues, application fees — usually $50-$75 each — can easily amount to more than a month of average household income (which, in 2012, was reported to be 833,000 tomans — or, roughly $680 for an urban family).[13] To highlight this disparity between average income, and the cost of university application fees — the PhD student quoted above, who claimed that application fees limit the number of schools students can apply to, and that it “happened to himself” — indicated on the survey that he only applied to two universities.

This does not include costs for the translation and mailing of school transcripts, and other application materials, which presents problems for students.

Mailing admission documents to US is time and money consuming. I spent more than $70 for mailing each admission document from Iran to USA. Because of sanctions, mailing documents is so difficult and expensive from Iran to US and vice versa.

— An Iranian PhD student in America

To be fair — some American universities do have policies allowing exemption of international students from application fees. Others do not, while some charge international students more. In reality, however, despite these differences — such policies are focused on what schools can get from students. Waiving an application fee, for instance, will increase the pool of international applicants — ensuring a higher number of students who might eventually pay full tuition. Obligating an application fee, on the other hand (even at higher prices than domestic students) — assumes that international students have the means to pay more. Very little of the time is it considered what can be given to students, and rarely is disadvantage taken into account. There are notable exceptions, however.

The University of Chicago, for instance, specifies that international students can receive an application fee waiver, “If your family makes less than or around $75,000 a year” — well beyond average annual household income in the developing world.[14] On the opposite end of the spectrum, however, the University of Massachusetts obligates payment of application fees for international students — even if it necessitates a bank transfer.[15]

The notion that a desire to study in America is indicative of socio-economic status fails to properly understand the US international student population, as will be explored.

There is no doubt that some universities will accommodate disadvantaged international students — but the fact is that no standardized system exists. Without such a system — as exhibited above, not only will students experience greater logistical burden, but it enables university administrators to be complacent about the hardships international students face, and be less inclined to empathize with them. Challenges with application fees are faced by students from all over the world, as the below testimony from an Indian student, on the MIT website, demonstrates:[16]

Simply, a desire to study in America is not indicative of financial solvency. And, most application fee policies seem to be geared towards foreign, undergraduate students — who it is assumed have the means to pay full tuition. However, this is a very limited understanding of the US international student population.

In fact, of the 765,000 international students who studied at American universities in 2012 — only 310,000 (less than 50%) were undergraduates. 300,000 (almost the identical number) were graduate students — while the remainder studied intensive English, or participated in professional training programs.[17] In 2012, according to the Institute of International Education (IIE) — over 80% of foreign undergraduates personally funded their education. However, among graduate students, 50 percent (one out of every two students) received funding from scholarships, university departments, or their governments.[18] At the higher echelons of education — the numbers are starker: In a 2011 survey of over 13,000 foreign doctoral recipients in the STEM fields, conducted by the National Science Foundation (NSF), 96% reported their “primary source of financial support” as coming from grants and fellowships, or teaching and research assistantships, rather than “personal funding.”[19] As a corollary to these statistics, according to the NSF, over 85% of Iranian STEM doctoral recipients from 2007-2011 (a total of 645 out of 755 surveyed students) reported the same.[20]

However, funding received is not necessarily indicative of financial status — many international students, regardless of funding level, experience financial hardship. Moreover, many students who are disadvantaged pay full tuition. In a February 2013 survey of nearly 1,000 Iranian students, conducted by PAAIA — The Public Affairs Alliance of Iranian Americans — only 40% of Iranian students were found to have received full-funding from American universities. Despite this — nearly all reported some kind of financial hardship during their studies. Simply, regardless of the funding international students as a whole receive — broad financial challenges can still affect them:

Over 90% of respondents noted that their finances were somewhat or extremely negatively impacted during 2012. Over two-thirds of the students said that the devaluation of the rial and restrictions on bringing money to the U.S. were the cause of their financial hardship. 62% of Iranians in the U.S. pay for their tuition and cost of living through support from their family in Iran or through a mix of scholarships and support from family in Iran.

A large majority (76.6%) of the students who took the survey indicated that they would accept any kind of financial help they could get, while 10% said that they were considering stopping their education and returning to Iran.

— “Iranian Students Facing Financial Distress in the U.S.” PAAIA. February 19, 2013[21]

In Iran, and many countries, higher education is provided free of charge. Therefore, high educational attainment, and a desire to study in America, are not indicative of socio-economic status — and by extension, the ability to pay application fees, or full tuition at American universities. In reality, lack of access to legal payment methods — coupled with the high cost of application fees — are some of the most pervasive challenges Iranian students face as they seek to study in America. While this fact cannot be changed — as it is the result of high-level, government-sponsored sanctions — by exempting Iranian students from application fees, its effects can certainly be eased.

Finally, to demonstrate all these points — below is a screenshot from an “application guide” produced by an Iranian student, and distributed online. Although the number of rejections might appear humorous, it demonstrates several poignant realities: The lengths that students will go to in order to leave Iran (the student below applied to 20 business schools in 4 countries); the central role of funding in university choice; and also the fact that paying application fees is simply the first step of the process, international students still have to be admitted to universities. Not only do students have to incur significant financial investment on the front end, but there is no guarantee of return (actual admission to a university).

Despite their logistical challenges — Iranian students must also invariably deal with the universal student experience of rejection from universities. However, in their case, it is particularly devastating news.

We can now better understand the “nerves of iron” that the PhD student was referring to. Given their physical inability to legally and easily conduct online transactions, the creation of an “international application fee waiver” — which is already in place for American students — could be an immediate, and painless step to significantly ease the financial, logistical, and emotional burdens of Iranian students on the path to American education.

Read Student Quotes About the Admissions Process

2. Standardized Testing

Although business relations between the West and Iran have been impacted by economic sanctions — American education testing companies have taken great strides to continue operating in the country.[22] In fact, the U.S. Department of the Treasury — which is tasked with sanctions regulation and compliance — specifically exempts universities (and by extension educational companies) from operating in Iran, and employing and paying local staff.[23] Simply, on some level — the United States government has indicated it has a vested interest in the education of Iranian students.

Therefore, the most common standardized tests are still offered in Iran: The TOEFL (English-language proficiency test) and the GRE (Graduate Record Examination). In fact, in 2012, nearly 7,000 Iranian students took the GRE — the fourth largest testing population, only behind the United States, India, and China.[24]

Despite this, several tests are not: Among them, the GMAT, LSAT, MCAT, and SAT. While Iranian students take all of these tests — in this section, the GMAT (Graduate Management Admissions Test) will be specifically covered. For more than a decade, business programs have attracted the highest number of international students to America, surpassing engineering.[25] Moreover, looking at the challenges of GMAT takers will encapsulate the problems of standardized testing as a whole in Iran.

Iranian students who wish to take the GMAT must travel outside the country for testing, and at great financial expense. While the GMAT is offered in 110 countries[26] — among the top 20 countries sending students to America, Iran is the only one without a GMAT testing center. Not only does the lack of GMAT presence in Iran hinder student mobility, but it most likely also hurts entrepreneurship in the country. The numbers support this claim: Only 4% of Iranian students in America (roughly 280 students) study business or management — the lowest percentage among the top student-sending countries.[27] This is a two-thirds decline from 1979, when 12% (over 6,000 Iranian students) studied business at American universities.[28] Simply, the number of Iranian students who formerly studied business, is nearly equal to the total number of Iranian students in the US today.

This lack of GMAT testing in Iran does not just harm American-bound students (as is the case with the SAT, LSAT, or MCAT tests), but, according to the Graduate Management Admission Council (GMAC), over “1,500 universities…in 82 countries use the GMAT exam as part of the selection criteria for their programs.”[29] In 2012, a total of 734 Iranian students took the GMAT exam, among them 278 women. This is a significant increase from 2008, when only 449 students took the test.[30] While this number of test takers is actually higher than many European countries, it also shows (compared to US enrollment numbers), the global nature of the GMAT. All business students in Iran — destined for North America, Europe, Asia, and Oceania — are affected. The following account from a female, Iranian student on a GMAT message board accurately conveys the challenges Iranian business students face:[31]

As it demonstrates, not only do Iranian students have to travel abroad to take the GMAT, and at great cost, but these challenges do not take into account if a student wants to re-take the test for a second time, in hopes of a higher score. According to GMAC, “repeat examinees” constitute “15 to 22 percent” of test takers.[32] Simply, if given the opportunity, 1 in 5 students chooses to retake standardized tests. The cost and logistical factors prohibit this for most Iranian students, and deny them an opportunity readily available to their peers in most other countries. Although, the above account does serve to exhibit the academic and personal determination of Iranian students.

Finally, the lack of standardized tests in Iran raises another complicated issue: The obligation of Iranian men, who have not served in the military, to submit a deposit to the government when exiting the country. Whether for tourism, standardized testing, an academic conference, a visa interview, or a study abroad opportunity — any time an Iranian male with no military exemption seeks to leave Iran, a letter from his university must be obtained, and an “exit security” (known as a vasighe) must be paid, in order to obtain an exit permit (khoruj az keshvar). The cost of this deposit varies based on the type of trip, and while they receive it back upon return to Iran, in all cases the cost is excessive and adds to the worry students face. In most cases, it is too much, and instead of a cash deposit, students must leave the deed to their house or car! For an “academic trip” (safar elmi), such as to an academic conference, it is 50 million rials ($4,000). For a “semi-academic trip” (safar nimeh elmi), to take a standardized test, it is 80 million rials ($6,500). And finally, a “non-academic trip” (safar gheir-e elmi) — which paradoxically includes study abroad to other countries — it is 150 million rials ($12,000), more than an entire year of household income.

This is not an isolated occurrence — Iranian universities have acknowledged this issue and provided guidance to students. Below is a screen shot from a PDF document on the “student affairs” website of the Islamic Azad University — the largest private university in Iran.[33] It displays not only the costs, but as can be seen in the midst of the Farsi letters — GMAT is clearly visible as one of the reasons why students would have to leave the country. The types of trip are in pink, with the costs in blue.

In addition to the challenges faced by students having to leave the country for testing — even TOEFL and GRE test takers inside Iran face problems. Not only are test costs sometimes prohibitive (and must be paid with a credit card, like application fees), but costly score reports must also be sent to universities. Every international student must take both the TOEFL, and a specialized test (GRE, GMAT, LSAT, etc.) for admission to American universities. Therefore, two tests must be taken, and two score reports need to be sent to each school. With the high number of schools Iranian students apply to — and an average of $20 to report a single test score — the costs adds up. However, unlike an application fee waiver, which already exists in some form, such a precedent does not exist to exempt students from these fees. Indeed, one student, in response to a self-administered survey, even noted that testing fees can hinder educational opportunities:

TOEFL is also kinda really pricy and many can’t afford it. The same for GRE. They cost $250…You can buy a motorcycle with that money.

— An Iranian PhD student in America, specializing in electrical engineering

Simply, Iranian students are stuck between a rock and a hard place when it comes to standardized testing. According to Education Testing Service (ETS) — which designs and administers the TOEFL and GRE, and describes itself as a “non-profit” — more than 50 million tests are administered annually.[34] While testing and score reporting fees help to fund test development, and the local staff and testing centers that exist worldwide — it seems clear that with a little philanthropic effort (a small dent, perhaps, in revenues from that 50 million number), Iranian students could be greatly helped. Testing fees for Iranian students would not have to be eliminated — but, taking into consideration their unique circumstances — they could certainly be lessened. Moreover, ETS already allows the free reporting of four initial TOEFL scores to universities (such an option is not available for the GRE, but could seemingly be implemented).[35] Extending this number of free reports could greatly benefit Iranian students. Another student expressed the financial burden of testing fees:

The prices are unbelievably high right now. When I was working as a full time civil engineer back home, my salary was 800,000 Toman per month. That time (2 years ago), registration fee for TOEFL or GRE was 250,000 Tomans. Right now the salaries are almost the same as before but the test fees are 900,000 Tomans. More than your 1 month income.

— An Iranian PhD student in America, specializing in civil engineering

In summary, the Graduate Management Admission Council (GMAC) can take a concerted step to administer the GMAT in Iran, which would not only ease student challenges, but also be a small, but important gesture in creating a positive culture of entrepreneurship, that as of now seems to be missing. And moreover, Education Testing Services (ETS) can significantly ease the financial burdens of Iran’s best and brightest, and expand access to educational opportunities, through a small price restructuring. With a few small steps, a lot of goodwill can be engendered, much suffering can be eased, and education in Iran can be promoted.

Read Student Quotes About Standardized Testing

3. Visa Appointments and Irregularities

To this point, a typical timeline in the life of an international student has been covered: Standardized testing, university applications, and admissions and funding. For Iranian students, as detailed, unfortunately these necessary steps are fraught with challenges. However, at the end of this process — for a select number of fortunate students — all of the financial and logistical challenges, hard work, and worry pay off: Not only do they receive a letter of admission to an American university, but many are also given full or partial tuition funding as well. After this process — it would be hoped that Iranian students can breathe easy, safe in the knowledge they will soon be studying a subject they love, in a free country. Unfortunately, however, for some it is only the start of even greater challenges and frustration.

More so than anything on the academic level (applications, testing, and admissions) — consistently, Iranian students report the greatest challenges during the visa acquisition process. Due to lack of diplomatic presence — after admissions to a US university, Iranian students must travel to an American embassy in a neighboring country (usually Turkey or the United Arab Emirates, among others) for a “visa interview.” While this in-person requirement can be waived in some cases — it is required for all citizens from countries considered “state sponsors of terrorism,” including Iran, Syria, Cuba, and Sudan.[36] Airfare and lodging costs make this the most expensive step for Iranian students. One student summarized the process:

After all those steps, application fee, taking the tests, finding professors for some funding (I still couldn’t get any funding for my PhD) it’s now the most important part which is visa application. For this part students and all the visa applicants that are from Iran should travel to other countries. Usually American embassy priority for accepting the application is the people of the country that embassy is located in…

They have our future in their hands…

And if you are too lucky and your application will be approved you should wait for unknown time, called clearance period, it is possible that the visa even will be rejected during this period.

After passing the clearance they have to travel again to that third party country to pick up their visa! So it goes without saying that it is such a big project.

— An Iranian PhD student in America, specializing in natural resources

Unfortunately, this cannot be changed. Simply, a lack of diplomatic relations between the United States and Iran will result in some challenges, on some level for Iranian students. A trip to an American embassy in another country — along with flights and lodging — is an unfortunate, but seemingly necessary part of that.

However, working within these strictures, the U.S. Department of State has taken concerted steps to streamline the visa process and ease experiences for Iranian students. Not only with the May 2011 decision to issue multiple-entry visas, but also the systemization of registration for visa appointments, and payment of consular fees, which came into effect throughout 2012.[37] In the past, students complained that Iranian-based travel agencies, in cooperation with local “brokers,” (or, “middlemen,” known as dalal in Farsi), often reserved visa appointment slots, and re-sold them to desperate students as part of expensive tour packages. Although students were routinely taken advantage of by such companies, some preferred it over the challenges of booking the appointments on their own. The situation became so dire that in 2010, an Iranian student designed a Firefox browser add-on, called the “Visa App Timer,” which would automatically register students for visa appointments when the form became available online. With the implementation of a new online system, usvisa-info.com — many of these challenges seem to have been recognized, and corrected.

However, to this day, some Iranian travel companies advertise “tours to the US Embassy in Ankara.” Even the website “embassyinterview.com” is a Farsi-language service promising visa interviews in Dubai, Armenia, and Cyprus. “Dalahoo.us,” the company above, sells packages “starting at $380,” not including a $140 “appointment fee,” along with lodging, and “invitation letters.”

Questions still remain, however. As referenced in the previous student quote — many Iranian students report having to travel not just once, but twice to regional US embassies. Visa clearance times — routinely between 1-2 months — mean that Iranian students must return home between their visa interview, and visa pick-up. Two trips must be made — two flights purchased — and, as covered, for Iranian men with no military exemption, two separate deposits to the Iranian government to exit the country. But, discussions with Iranian students indicate this policy varies by embassy. Allegedly, certain US embassies allow “friends” to drop-off passports, and pick-up visas for approved Iranian students, after the clearance process. Others do not allow this — or, students do not have “friends” travelling outside of the country at the time needed — necessitating a second, costly trip outside the country. In some cases, the same “middlemen” who book visa appointments also charge fees to transport Iranian passports out of the country, and employ local “brokers” for drop-off and pick-up. While there are similar, personal drop-off and pick-up requirements at US embassies around the world, standardization and easing of the visa pick-up process at regional embassies and consulates could greatly ease the logistical and financial burdens of Iranian students. As one student remarked — questioning why in-person pick-up is necessary after the visa interview and clearance process has already taken place: “We would be happy to pay the postage fees.”

Finally, on the same issue, because “visa interview at the US embassy” is not a valid reason for exiting Iran — most students (who have not served in the military) have to depart under the guise of an academic conference, significantly contributing to student stress. On top of this, it can be difficult for such students to even obtain a passport, or official copies of their transcripts (resulting in the need to pay a reshve, or bribe). Because many graduate students receive admissions decisions in the spring — coinciding with the official, month-long Nowruz new year holiday in March — receiving the forms and permissions necessary to leave the country for visa interviews and pick-up can be delayed, further frustrating students. In December 2011, the United States government established a “virtual embassy” in Iran.[38] Although there would be many impediments, student feedback was clear: In an era of Skype — perhaps this virtual component could be implemented in reality, and extend to visa interviews, as well.

Multiple-Entry Visas and Clearance Times

As covered — the American government has taken clear and concerted steps to ease the mobility experiences of Iranian students. In May 2011 — after nearly a year of lobbying by Iranian student groups, university and college graduate associations, and Iranian-American advocacy organizations — a high-level decision was made to begin issuance of multiple-entry visas to Iranian students, which would normally only result from “reciprocity” on behalf of the other country. In addition to the statement by Secretary Clinton, the rationale behind the change in visa policy was also articulated by the US “virtual embassy” in Iran:

As President Obama noted in his Nowruz (Iranian New Year) statement, on March 20, 2011, Iran’s young people carry with them the power to create a country that is responsive to their aspirations. He pledged U.S. support for Iran’s young people, and this is an example of that support. Making these adjustments to our visa policy reaffirms the President’s pledge and will help build new avenues for engagement with Iran’s youth, facilitate their ability to study in the United States, and allow Iran’s young people to better interact with the rest of the world.

— “Changes to Visa Validity for Iranian Student Applicants in F, J, and M visa categories.” U.S. Department of State.[39]

However, the push for multiple-entry visas began a year earlier, in 2010, by an engineering PhD student at Southern Methodist University (SMU) named Ali Moslemi. Having returned to Iran in 2009 over winter break, to visit family he had not seen in over four years — Ali’s application for a re-entry visa was delayed at the American consulate in Dubai. Weeks dragged on, and Ali consequently missed spring classes, graduation, and the chance at a valuable teaching assistant (TA) position. Upon intervention from Texas Senator John Cornyn, the process was expedited, and in September 2010 — nine months after he left SMU for a short vacation — Ali returned to Texas.[40] In response to his experience, Ali started MEVisa.org (“Multiple-Entry Visa”), and compiled similar stories from Iranian students about the challenges of student life with single-entry visas.[41]

Additionally, MEVisa launched a petition, and conducted a survey of 1,100 Iranian students in the US. The response was unequivocal: Over 80% of students indicated that the “single entry visa policy affected studies or research in a negative way.” 60% indicated that a family emergency had occurred, but that they could not return home due to fear of re-entry complications. Moreover, 36% of students (every 1 in 3) reported that the “visa clearance” time to obtain their original visas had taken from “between 3-4 months” to “more than 6 months,” often resulting in university deferments by a semester or more.[42]

As the numbers demonstrate, the issuance of single-entry visas significantly impacted the well being of the majority of Iranian students in the US.

News of MEVisa spread throughout the Iranian student community, and made its way to NAGPS — The National Association of Graduate-Professional Students. In cooperation with Iranian-American lobbying groups, the issue was raised in Washington, and the notion emerged that helping Iranian students could not only alleviate mobility burdens, but also help advance positive change within Iran.[43] In May 2011, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton addressed Iranian students directly in a video, announcing the new change.[44] Although the decision was not retroactive (it could not be applied to students already in the US), Iranian students admitted to university programs in “non-sensitive, non-technical” fields became eligible for multiple-entry visas to be issued at American embassies and consulates in the region.[45] For reference, this delineation of academic fields into “sensitive” and “non-sensitive” is from the “Technology Alert List” (TAL), a U.S. Department of State guideline concerning “critical fields” pertaining to dual-use technologies, and used in the evaluation of visa applicants.[46]

Since May 2011, two things have happened: Ali has gotten married, his spouse has successfully immigrated to the US, and he has secured a stable job with an oil company in Texas — no small feat, given the challenges graduates face changing from a student to work visa. Also a big change given that he was almost barred from entering the United States. Secondly, Ali has also assumed leadership of the Iranian Students and Graduates Association (ISGA). And, in April 2012, a year after the multiple-entry visa decision — ISGA conducted a new survey of incoming Iranian students, to assess implementation of the multiple-entry visa policy.[47]

Despite being a major initiative, the survey results are decidedly mixed. Clearance times for Iranian students have decreased considerably. Rather than 36% — only 22% of students reported that visa clearance took “between 3-4 months” to “more than 6 months.” Visa clearances of “one month or less” also significantly rose, from 29%, to 45%. Although there are still considerable wait times for some students, the numbers indicate that the visa issuance process is being streamlined.

However, some shortcomings and inconsistencies were still found — not only in the issuance of multiple-entry visas, but in embassy implementation of the new directive. According to survey data, only 25% of students (1 in 4) received multiple-entry visas, despite entering the United States after May 2011. As covered in the introduction — STEM students, engineers in particular, constitute the majority of Iranian students in the United States. Despite this, the survey found that only 17% of “engineering and science” students received multiple-entry visas. Moreover, overall, only 29% of women surveyed received multiple-entry visas.

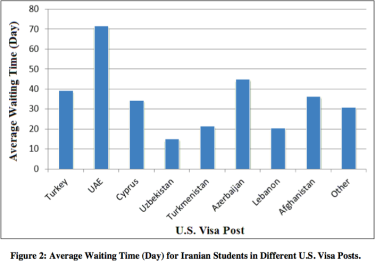

Additionally, the survey discovered wide discrepancies with the issuance of multiple-entry visas based on the embassy where the student applied, with similar discrepancies concerning clearance wait times.

The overall findings were succinctly summarized by the survey administrators. Simply, those posts with the longest clearance times also had the lowest issuance rates of multiple-entry visas. Those that granted the most multiple-entry visas, consequently also processed visas the fastest:

The survey results were filtered based on the place of interview and surprisingly it was found that the visa number of entrance is highly dependent on the visa issuing post. While near 100% and 70% of visa applicants who had interview in Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan respectively received multiple-entry visas only 10% and 20% of visa applicants who went to UAE and Turkey respectively received multiple-entry visas. The average waiting time for visa clearance was 49 days which again was found to be dependent on visa issuing post. Students who went to the U.S. consulate general in Dubai for interview waited on average about 70 days while students who went to the U.S. embassy in Tashkent waited on average about 15 days.

— “Survey Report on the Multiple-Entry Visa Policy Implementation for Iranian Students and Scholars.” Iranian Students and Graduates Association (ISGA). April 2012[48]

Unfortunately lack of publicly available, concrete data impedes further discussion of these consular issues. However, there are several potentially concerning elements — particularly the low rate of multiple-entry visa issuance to women, and the theoretical connection between visa type (beyond the issuance or non-issuance of a visa), and propensity for technology transfer. However, it is clear that positive strides are being made. And, in one area (visa pick-up), a positive and proactive change can be made to ease the experiences of Iranian students.

The survey also noted that while only 17% of “engineering and science” students received multiple-entry visas, 74% of “arts and humanities” students did. As referenced, because of dual-use technology fears, STEM students — especially from countries considered state sponsors of terrorism — do face more scrutiny and longer visa clearance (“Visas Mantis”) times. However, it is clear that visa issuance authorities are still wary of Iranians who study in the STEM fields. And, this should not be the case for the vast majority of students. If anything could be done to normalize how Iranian engineers and scientists are perceived, it would be this:

- Engineering and science students from Iran are the “normal majority.” Every 3 in 4 Iranian students in the United States studies in the STEM fields, the highest proportion of any country.[49] Moreover, engineering has overwhelmingly been the #1 field of study for Iranian students, since the 1950s.[50] Historically, engineers have represented the largest percentage of foreign students from the Middle East, and until recently (as it was overtaken by business and management) most of the world.[51] Even today, among Saudi Arabian students (the largest Middle Eastern group in the US), after intensive English, the largest field of study is engineering. Today, 58% of Iranian students in the United States study engineering, dwarfing the next country, India, at 36%.[52]

- According to the National Science Foundation (NSF), a U.S. government agency which conducts an annual survey of doctoral recipients in the STEM fields — in surveys from 2005-2011, on average 89% of Iranian students indicated they would prefer to stay in America after graduation, the highest number of any country.[53] By comparison, only 10% of Saudi students indicated the same — the lowest of any country. Fears of technology transfer by engineering and science students returning to Iran — which fuels the single-entry visa issuance policy — are not broadly supported by statistics.

- Finally, of the total Iranian PhD recipients in the STEM fields since 1990 (roughly 2,100 students) — only 329 have been women (an average of 16%). In 2011, of 186 overall STEM doctorates awarded to Iranian students — 41 were women (roughly 22%).[54] These statistics are not just for engineering, but all high-level STEM doctorates. The decision to deny multiple-entry visas to nearly 70% of surveyed women — while Iranian women overall represent a small number of STEM doctoral graduates — is not defensible given the facts.

On this note, it is also important to emphasize that the “stay rate” of a student community is not a value judgment. On the one hand, statistics make it clear that the “push-pull” factors are keeping Iranian students in the United States after graduation. This mitigates the perceived “threat” of technology transfer. However, it also means that these students are not returning home, to mentor and educate a new generation of students in Iran, and perhaps serve as catalysts for institutional reform and change. Moreover, in purely economic terms, massive “brain drain” is occurring. Simply, on many levels, the notion that student exchange will serve to “fuel change in Iran” is problematic. However, with the overwhelming concern at hand — fears of technology transfer — the numbers do not broadly support such a notion, necessitating the broad denial of multiple-entry visas to science and engineering students. Lastly, as mentioned, one of the largest questions is how type of visa issued (beyond issuance or rejection of a visa), has any correlation to the propensity for technology transfer. Rationally speaking, international student graduates with jobs in the United States could eventually return to their home countries with transferable skills beyond those learned in the classroom. And, even single-entry visa recipients return to their countries at the end of studies. Simply, the connection between visa type, and technology transfer, appears tenuous. There is no “right answer” — whether students stay in the United States after graduation, or return to their home countries, each produces a wide range of positive and negative effects, in different areas.

In closing, single-entry visas simply seem to cause hurt — they mitigate nothing, except the ability to easily return home for holidays to see loved ones, and to attend academic conferences (often important for career development). In interviews with Iranian students, those who had received multiple-entry visas expressed thankfulness, and indeed some have even gone home to visit family during the course of their studies. However, for single-entry visa recipients, the sentiments are clear:

This type of visa practically imprisons the person inside the US, because if the student exits the country, he/she should apply for a visa again, which is so risky that may prevent the student from continuing his/her education. That is why many students tend not to exit from US, causing lots of personal, emotional, etc. problems.

— An Iranian PhD student in America

Read Student Quotes About the Visa Process

4. Women

For many international students — education functions as their sole key to the world. For some, scholarships and university funding open the door to a global world that had previously been beyond financial means. For others — especially those from countries with broad visa and travel restrictions — the opportunity to study abroad serves as a means of legitimate travel, to experience an outside world that had been largely out of reach. And finally, for others — international study opportunities provide a means for social mobility and respect, previously denied to them, or thought impossible or untenable.

For women from the developing world, and especially traditional societies — higher education attainment encompasses all of these, and is a transformative force within families, and society. It promotes social tolerance and respect for diversity of opinion, forges notions of gender equality and meritocracy, and brings about changes in social relations and human rights. For women who study abroad — these effects are even more pronounced. It is for these reasons that educational exchange with women in the Muslim world should remain a top priority for educators, university administrators, and policy makers.

In the context of Iran — all of the above is true. However, Iranian women face unique issues when studying abroad, and are greatly impacted by the challenges Iranian students face as a whole. While many cannot be solved — by documenting them, it is hoped that student mobility for women, and general issues facing Iranian students, can come better into focus.

Statistics

Iranian women have a long history of higher education in America. A 1946 survey of Middle Eastern students records the names of 117 Iranians at American universities — among them ten women.[55] They studied journalism, music, home economics, intensive English, and agriculture. However, from 1950-1980, Iranian women constituted only a fraction of the total Iranian student population. In 1979 — at the peak of Iranian student enrollment in the US — 80% of students were men. Only 20%, or one out of every five, was female. However, this rate was not much different from other countries.[56] Interestingly, women’s participation in study abroad actually increased after 1979. In 1990, the Institute of International Education (IIE) issued the last of its “Profiles” series of international student reports — which, unlike the “Open Doors” publications of recent years — reported the gender data of international students. In ten years, the percentage of Iranian women had increased to 33% — one in every three students.[57] Where does this put the number of Iranian women today?

Unfortunately, contemporary gender statistics on international students in the United States are unavailable — a significant shortcoming in public data collection, especially given the educational initiatives focused on women in the Muslim world. However, there are indications that this rate from 1990 has largely remained the same. The MEVisa survey, discussed in the previous section — which was distributed to 1,100 Iranian students in 2010 — had a response rate of exactly 66% men, and 33% women — identical to the 1990 “Profiles” data.[58] The ISGA survey, distributed in 2012 (only to a sample of 175, as it focused on incoming students alone), similarly had a response rate of 69% men, and 31% women.[59] Simply, based on this data, women seem to constitute roughly one-third of current Iranian students in America (from the 2012 total of 7,000 students, around 2,300). While this is not a statistically ironclad argument — it supports the assumption that the dynamics of Iranian female participation in American education have remained largely the same following 1979.

Therefore, what does the 1990 “Profiles” data tell us about what female students were studying? Unfortunately — the data presented is not direct, but it can be extrapolated.[60] Among Iranian female students in the United States — the most popular degree fields were Health Science (19%), Physical Sciences (17%), Math and Computer Science (13%), Engineering (12%), and Business (8%). However, this does not take into account disparities between males and females in certain fields. For instance, while 12% of women overall studied engineering, compared to fellow Iranian women in other fields — men accounted for 87% of overall Iranian student enrollment in it. Moreover, although statistically more Iranian women than men studied in the humanities (54% v. 46%), as a field of study humanities accounted for just 3% of total female student enrollment, and less than 1% of total overall enrollment. Due to the changing natures of these fields (especially computer science), it is likely that these numbers have shifted. However, overall, we can see how Iranian women have contributed to the fact that every 3 in 4 Iranian students studies in the STEM fields — simply, they are very scientifically minded.

Unique Issues Related to Women

All Iranians — whether male or female — face the same challenges during the study abroad process. They must pay prohibitive application and testing fees, negotiate high bureaucratic, financial, and logistical burdens, and travel outside of the country for visa interview and pick-up. However, knowledge of these steep hurdles often serves to dissuade women and their families that study abroad is an option, even before the application process occurs.

As will be covered in the next section — higher education in Iran has existed for less than 75 years. Prior to the establishment of primary and secondary schools in the mid-1920s, and into much of the mid-20th century, literacy rates hovered at around 20%. For women, this number was significantly lower. Simply, despite the fact that Iran has experienced massive social change and female educational attainment over the past 40 years — it is still a socially conservative country, that not long ago saw limited social mobility for women. Even in the US — if confronted with the prospects that Iranian students have to go through, most families would balk at the prospect of their children studying abroad. Many Muslim families in the developing world, under the best of conditions, hesitate in sending their daughters abroad for education. Given the well-known burdens involved in the process, simply, before many Iranian women even apply to American universities, their plans are dead in the water.

For women in the Muslim world, study abroad at an accredited institution serves as a legitimate means to travel and gain the experience, confidence, and feelings of self-worth and assuredness that come with living alone and negotiating daily affairs. Without the “excuse” of education to socially legitimize this process, such a prospect is largely impossible. Moreover, for many Iranian women, education is not only a means to leave home and experience the freedom of the outside world, but also escape the burden of social and religious conditions in Iran. With the impediments faced during study abroad, education has been limited as a means to do this. When foreign education is accompanied by significant challenges, like in the case of Iranian students — it loses its legitimacy to function as a force for social betterment and change. Education outside of the country can be derided by already skeptical family members — who might be willing to consider it under better conditions — and closed off as an option.

In addition to these realities — specific logistical issues do exist for Iranian women. In order to leave the country, women need the permission of a male guardian (usually the father), and in some cases, must be accompanied by him. In many cases, simply by choice, a male parent or sibling travels abroad with them, as any family might want. Therefore, testing, and visa interviews and pick-up, require that two flights be purchased — adding to the heavy financial burden incurred during travel abroad for the visa process, and the application process in general. As one female, PhD student expressed:

I went to take my visa with my dad because in Iran they will not allow you as a single girl to go out without your dad or brother or your husband. It cost me almost $2500 at that time but I am pretty sure it would be more expensive now because of Iranian currency depreciation.

— A female, Iranian PhD student in America, specializing in life sciences

Money Transfers

While many Iranian women do study in scientific fields, female students in general are known to predominate in many non-technical fields, including languages, arts, education, and humanities. In these fields, funding opportunities from universities, comparatively, are significantly less. Although statistics are not readily available, it is assumed that more female international students would need to pay partial or full tuitions. And, this introduces another problem referenced in the introduction: The inability of parents in Iran to easily send money to their children, for food, rent, tuition, and emergencies.

As will be discussed in the next section, Western-backed sanctions have effectively isolated Iran’s banking system from the world: Not only the ability to conduct credit card transactions facilitated by Western banks (such as on the Internet), but also traditional bank transfers between Iran and the US. Unfortunately, sanctions law is poorly understood even among experts, and conflicting information exists as to if bank transfers are actually illegal under US law. However, the fact is that American banks have hedged their bets, and rarely authorize transfers between individuals in Iran, and the US. Banks in third countries that authorize transfers from Iranian accounts, to be sent onward to the US (known as “u-turn” payments), are now also subject to sanctions laws.[61] Simply, many Iranian students (male and female alike), step off the plane in America with significant amounts of hard currency, in order to fund semesters, or years of tuition payments and living expenses. While other options for money transfer exist — such as “hawala,” an informal process which charges significant interest, and is more popularly known to be associated with criminal groups — simply, life is made very hard for Iranian students abroad. Alternatively, hard currency can be given to a friend or acquaintance who is travelling abroad, for further transport to the United States, or direct deposit in banks abroad, mitigating “u-turn” laws. This reality was even expressed by “EducationUSA Iran” — a government-funded educational support service tasked with helping guide Iranian students through the American university application process (as will be covered in the next section):

Iranian banks do not issue credit/debit cards nor facilitate wire transfers. Some students find a “middleman” who charges a commission to make the online payments for application fees on their behalf. These transactions are not issued through Iranian banks; rather they are done through banks in third countries or relatives and friends that are living outside Iran. Students without a “middleman” or contacts outside of Iran typically request that the U.S. institution waive their application fee. Later, when they have traveled to another country for their visa interview and stamp, they can transfer the money in order to pay the tuition and fees.

— “Finances.” EducationUSA Iran[62]

Many conveniences American students rely upon when studying in foreign countries — like the ability to receive rapid bank transfers from parents back home — are simply not options for Iranian students. Therefore, fathers must send their daughters abroad not only with significant amounts of dollars (which, as covered, are extremely difficult to obtain, and “expensive” to purchase with Iranian currency), but aware that in an emergency, there is little that can be done to quickly aid them. Also, the deteriorating exchange rate between the US dollar and Iranian rial means that even if families in Iran want to help, they often cannot afford to do so. One student tragically remarked:

My father lost his job and cannot afford the cost of my life in US anymore. His money has no value anymore because of the drop in our currency.

— “Iranian Students Facing Financial Distress in the U.S.” PAAIA. February 19, 2013[63]

Another Iranian student — a woman pursuing a master’s in engineering management at Duke University — conveyed her financial situation:

Duke is a very expensive university anyway…so it’s become a huge stress on my family, how they are going to provide this money for me. They have to buy really expensive dollars, and you can’t ever predict what will happen in Iran. Every day the exchange rates change.

— “Currency crisis hits Iranian students in the U.S.” Latitude News. October 19, 2012[64]

Similar sentiments were expressed by another student, in response to a self-administered survey:

As I am supported by my family, the current sanctions caused a significant drop in our currency (Rial). This increased about 3-4 times the amount of money that my family wanted to send for me. Now it is getting so difficult for them to support me here.

— An Iranian PhD student in America

One student expressed frustration about having funds in Iran — but being unable to gain access for tuition payments:

This decision is affecting me directly because I can’t transfer money from my country…I have money in my account back there, but it’s tied up, and I can’t do anything. It’s very frustrating.

— “Exchange Students Suffer from World Tensions.” Royal Purple News. February 8, 2012[65]

Seemingly, this also includes the often high and unexpected payments for medical bills or hospital stays that can stretch already frayed budgets. It is highly unlikely that an Iranian student in the US would experience a life threatening situation due to these financial restrictions. However, life is not made easy for them, either. And, for students — who have dreams, aspirations, and hopes like our own, and have already gone through years of significant expense and worry to come to America, leave an oppressive environment, and better themselves — this added detail (along with single-entry visas) ensures that their stays in the United States are also fraught with challenges. Though it is not likely, a system is needed that could allow the quick, and legal transfer of funds between parents, and Iranian students in good standing at American universities. PAAIA — The Public Affairs Alliance of Iranian Americans — recently advocated a solution to the situation:

1) Grant special student relief for Iranians studying in the U.S. consistent with previous emergent situations, 2) ensure that applications for off-campus employment based on severe economic hardship are expeditiously processed, and 3) waive the application fee for these students when applicable.

— “Iranian Students Facing Financial Distress in the U.S.” PAAIA. February 19, 2013[66]

In closing, one Iranian student, in response to a self-administered survey, expressed his wishes:

For some students like me that are semi-funded by their advisers, sending money from Iran to the USA is almost impossible, and it is scary because I always think if I ran out of money what should I do? I think the USA government should enhance some facilities for transferring money for Iranian students.

— An Iranian PhD student in America, specializing in life sciences

A History of US-Iran Educational Engagement, 1949-Present

Understanding the history of educational exchange and cooperation between the US and Iran has little bearing on the problems and issues faced by Iranian students today. However, it can impart an important lesson: The Iranian people have not changed. Governments have. Almost a century ago, the first Iranian students came to America. For nearly a decade in the 1970s and 80s — Iranians were the largest foreign student group on American campuses, and over 30 US universities had student and scholarly exchange agreements with Iranian counterparts. The desire for higher education and the acquisition of knowledge among students span the limitations and constraints of governments and politics. The history of educational engagement between the US and Iran can demonstrate this, and lend credence to the fact that student engagement should be treated separately from prevailing geopolitical conditions.

Educational Exchange, Literacy, and Development

Paradoxically, Western educational exchange with Iran began long before the establishment of higher education in the country. Throughout the 19th century, Iranian students traveled to Europe in pursuit of education.[67] In the United States, the earliest records indicate that 22 Iranian students were enrolled in American universities in 1924.[68] The University of Tehran, Iran’s first institution of higher learning, would not be established for another ten years.

Higher education in Iran is less than a century old. Although the University of Tehran was founded in 1935, it was not until 1949 that the Universities of Tabriz, Isfahan, Mashad, and Shiraz were founded. Primary and secondary schools were established in the mid-1920s, and in its second year of operation, the University of Tehran only enrolled 1,300 students.[69] Nationwide, the literacy rate was estimated to be 10 percent, a negligible proportion among women.[70] Simply, Iran was in dire need of development.

In the years following World War II — Iran joined the Central Treaty Organization (CENTO), along with Iraq, Pakistan, Turkey, and the United Kingdom — which was formed to contain Soviet expansion in the region. Concurrently, President Harry Truman authorized the Point Four development program in Iran, to be administered by the Technical Cooperation Association (TCA).[71] Quite rapidly, the process of development began, and the GNP increased by 10% annually. Moreover, Iran’s imperial government increasingly looked towards America as an ally. In 1960, Iran was one of the first countries to accept Peace Corps volunteers, who established libraries, and taught English-language programs to school children. Slowly, development began, and education was considered a central part of it.

Within this general development scheme, formal, educational exchange agreements between the US and Iran were also signed. In September 1949, the “United States Commission for Cultural Exchange Between Iran and the United States” was formed, which sought “to promote further mutual understanding between the peoples of the United States of America and Iran by a wider exchange of knowledge and professional talents through educational contacts.”[72] A staff of four Iranians and four Americans were assigned to “facilitate educational and cultural programs and activities.” Re-signed in 1963, it also allocated federal funds for student exchange — not only for Iranians, but for American students and scholars to study, teach, and do research in Iran. By 1969, 4,500 Iranian students were studying at American universities. And by 1976, 32 American universities and colleges had exchange agreements with 15 Iranian universities.[73]

However, the next 10 years would produce a dramatic rise the number of Iranian students in America. Within a decade, over 50,000 Iranian students would be studying on American campuses. In the 1979-1980 academic year — when the Islamic Revolution in Iran occurred — this number reached its peak, with 51,310 Iranian students at American universities. This was three-times that of Taiwan, the second largest student-sending country, with 17,000 students (though, more per capita given Taiwan’s population).[74]

What triggered this sudden rise in Iranian students? Evidence of an educational or diplomatic agreement which prompted this significant increase in students is hard to come by. Largely, the agreements of 1949 and 1963 — to generally promote student exchange — seem to have created an environment where educational exchange between the US and Iran was acknowledged, both diplomatically, and for development purposes. Interestingly, facts point to two reasons for this sudden shift in student numbers: Funding, and demographics.

According to a 1972 report by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), roughly 78% of Iranian students in America were self-supporting.[75] However, by 1977, this number had decreased to 50 percent.[76] Simply, at the peak of enrollment, one in every two Iranian students at American universities was being supported by the Iranian government. In 1958, Reza Shah Pahlavi established the Pahlavi Foundation — a self-described charitable, non-profit organization, which advanced social services inside Iran, and was the beneficiary of several hundred million dollars in direct investment. Starting in 1977, the Foundation began assisting exchange students with direct cash grants, and loan assistance — effectively financing the American educations of 12,000 students.[77]

Secondly, there is an issue unique to Iran in the 1970s: The spread of education that had occurred because of development efforts over the previous 30 years created a vast new, educated class of young people, eligible for university education on a scale never before seen in Iran. Although domestic universities had been established by this time, the influx of eligible participants guaranteed a higher proportion of students desiring education abroad. One report from 1976 made a seemingly prophetic prediction:

There are currently more Iranian students — estimates vary from 15,000 to 20,000 — in U.S. universities and colleges than from any other country. This demand for training in the U.S. is likely to expand over the next five years because of the explosive increase in the output of Iran’s secondary school system. For example, the number of secondary school graduates in Iran increased by 30 percent in 1976. Although the number of university openings is expanding in Iran, a large number of Iranians will pursue their academic training in the U.S. and Europe over the coming five to ten years.

— “An Analysis of US-Iranian Cooperation in Higher Education.” American Council on Education (1976), p. 134[78]

Indeed, from 1935-1965, enrollments in secondary education increased from just 16,000, to almost 500,000 students.[79] This also means that unlike today — the majority (75%) of Iranian students in 1979 studied at the undergraduate level.[80] While these factors fueled a desire for foreign education — it is now generally acknowledged that this rapid development led to significant alienation and social stratification, which, along with crackdowns on political dissent and personal liberties (variant political ideas themselves incubated in universities) by the Shah, led to the Islamic Revolution in 1979. And with that — Iran withdrew from CENTO, Ayatullah Ruhollah Khomeini consolidated power around the idea of an Islamic theocracy, and diplomatic relations with America were permanently severed.

In the lead-up to and wake of the Islamic Revolution in Iran, Iranian students in the US came under increasing scrutiny. Concerns over the pervasiveness of anti-Shah protests — a stalwart American ally — and Iranian opposition groups on American campuses, prompted President Jimmy Carter in November 1979 to authorize the “Iranian Student Registration Program.” In one month, from November-December 1979, Immigration and Nationalization Service (INS) agents conducted interviews, and confirmed the academic and visa standings of 56,694 Iranian students — several thousand above the enrollment number reported by American educational surveyors.[81] Indeed, this is the true number of Iranian students at American universities in 1979-1980. While nearly 7,000 were found to be out of status, and deported — others lost the government stipends which funded their studies, and experienced financial hardship. This even affected some educational institutions when in December 1978, Windham College, in Vermont, was forced to close when the tuition payments from Iranian students stopped. With only 150 American students, the college’s 75 Iranian students were a major source of revenue.[82] With the Iran-Iraq war occupying much of the 1980s, where university-age men were sent to fight, along with the ideological “cleansing,” restructuring, and closure of universities for several years following 1979, and travel restrictions — the tap of Iranian students was slowly turned off, which continued to be the case until relatively recently.

Current Policies and Sanctions

In the wake of the Islamic Revolution and Iran hostage crisis, sanctions quickly followed. Executive Orders 12205 and 12211 issued by President Carter in April 1980, prohibited commercial trade with Iran, and the importation of Iranian goods.[83] However, it was not until the mid-1990s, when President Bill Clinton signed two further executive orders, that virtually all transactions between the US and Iran came to an end, including banking and financial transfers.[84] In the mid-2000s, with growing concern for Iran’s nuclear aspirations, the United States Congress passed into law the “Iran Freedom Support Act,” which amended the “Iran and Libya Sanctions Act” (ILSA) of 1996. This was followed, in 2010, by the “Comprehensive Iran Sanctions, Accountability, and Divestment Act.” And, in 2012, the “Iran Threat Reduction and Syria Human Rights Act.”[85]

In addition to reaffirming broad financial sanctions, the Iran Freedom Support Act authorized “assistance to support democracy in Iran:”

The President is authorized to provide financial and political assistance (including the award of grants) to foreign and domestic individuals, organizations, and entities that support democracy and the promotion of democracy in Iran.

— Sec. 402, Iran Freedom Support Act, 2006[86]

Given the growing sanctions legislation and regulations, the “Office of Foreign Assets Control” (OFAC) at the U.S. Department of the Treasury, in 2010, promulgated the Iran Transactions and Sanctions Regulations (ITSR), which sought to systemize the limits of American financial and economic engagement with Iran.[87] However, given the mandate to support democracy in Iran, some activities were exempt from sanctions: Namely, university partnerships, and “academic and cultural exchange programs.” As noted in the title of the text — democracy, human rights, and student exchange had now been linked together.

Pursuant to these general trends, in August 2007, the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs (ECA) at the U.S. Department of State, in cooperation with AMIDEAST, incepted the “EducationUSA Iran” program — now administered by the Institute of International Education (IIE). Although EducationUSA programs existed for a variety of countries, with local advising centers — through their website (EducationUSAIran.com), a concerted effort was made to engage Iranian students, and guide them through the university application, and immigration processes. Podcasts and information guides in Farsi were developed to offer accurate information about education in the US. Although not directly related to the establishment of EducationUSA Iran, it is at this time that student numbers from Iran began to slowly increase from their gradual fall after 1979. Simply, Iranian students were on the radar, and higher education in America was being actively promoted.

As exhibited in the Iran Freedom Support Act, democracy promotion in Iran was on the US government radar prior to 2009. However, after the summer 2009 election protests in Iran, and subsequent crackdown — the rhetoric and support were significantly ramped-up. Iranian students — dissatisfied with the political and social environment at home — not only had a greater desire to leave Iran, but the general will and acknowledgement also existed. This helps to explain the rising numbers of Iranian students since 2007, but which has been especially accelerated since 2009-2010, and is still occurring today. As mentioned, since 2008-2009, there has been a 100% increase — a doubling of students — from 3,500, to 7,000. Moreover, between 2008-2009, and 2009-2010 alone — roughly following the crackdown in Iran — there was a 34% increase in students.[88] Simply, Iranian students wanted to leave, the capacity existed to acknowledge and assist them, and their fate had become conflated with the fate of human rights and democracy promotion in Iran. However, there are indications that the number of Iranian students in the United States is higher than the “official” numbers reported by the Institute of International Education (which relies upon voluntary reporting of data, and only from specific types of schools). In 2012, the U.S. Department of State issued 3,024 F-1 student visas to Iranian nationals — which, when factored in with the numbers from previous years, puts the actual Iranian student population somewhere between 8,000-9,000 students, if not more.[89]

Therefore, given this level of general support, the significant financial, logistical, and consular challenges Iranian students have faced when seeking to apply and travel to American universities seems especially incongruous. And this is where we find ourselves today.

Stakeholders